20 Oct Errors eat earnings

Analysis of decades of accidents has helped us objectively quantify fire risks and the construction industry has been engineering solutions to address these. Iterative revisions of fire and life safety strategies have helped save countless lives and millions of dollars. But as the complexity of buildings, contracts and supply chain of materials has been increasing, implementing these strategies is becoming more difficult explains Abhishek Chhabra, Market Development Manager, Thomas Bell Wright International Consultants.

The building blocks of implementation, Technical Specifications and Commercial Contracts, are where the trouble often starts. The fatal error of copying texts from specification documents written in a given jurisdiction for a given type of building to another is just one of so many possible errors that lead gullible businesses from profit to loss in no time.

Liabilities and profit leakage

Incorrectly defining what you want to buy, is committing a Himalayan blunder. While a lot is spent on awareness for people buying consumer goods, business to business transactions expect the procurement teams to be well aware of all risks. The commercial impacts of accidents are often huge as compared to the cost to avoid them in the first place. Before considering errors in specifications and contracts and how they can open the door for liabilities that can eat up the profits, let us explore some numbers with an example of a 200 room five-star hotel in the region.

The cost to build such a hotel is estimated around 400 Million AED. If the façade is not too ostentatious; its cost including everything would be ~ 28 Million AED. The cost of the doors package can be estimated ~ 4 Million AED and the fire doors with hardware would cost less than a Million AED.

Getting the contract for supplying building materials like Aluminium Composite Panels (ACP)/ Façade facing materials or fire doors for a prestigious hotel chain also adds to the marketing campaign of material suppliers. This can motivate sellers to keep very low profit margins and hence the potential risk of the supply of materials complying to just what is asked for in the specifications and the contracts.

Based on certain assumptions of occupancy rates and average daily rates; such a hotel would earn between 70-90 Million AED per year from revenues of rooms, restaurants, banquets etc. Without factoring in cost of land, the earnings after removing operators expenses, the earnings before interest, taxes, and amortisation for such a property can be estimated to be about 20-30 Million AED a year. A fire incident which could be contained within the compartment with, for example, proper fire doors would normally close the hotel for about 12 months, bringing bring down the occupancy levels in the future. Without even considering the cost of the bad publicity and liabilities the math is really simple. Just looking at the cost related to procurement of fire doors; it is easy to understand the value of correctly specifying and procuring fire safety related goods and services right from the start.

Procuring for fire safety

All fire and life safety plans will fail if the products and services are incorrectly procured for their implementation. Specifying the compliance of products and services requires correct understanding of the language and terminology. If a mobile phone buyer is ignorant of the terminology quantifying battery life or defining camera resolution they would be in a position of disadvantage. But if the specifier or procurer of a fire door does not understand the difference between a ‘test report’ and a ‘certification & listing’ or is not aware what a ‘fire-door label’ signifies, the possible repercussions would be manyfold for the liabilities and profit /loss of the companies they are working for. Recall the earnings of the hotel versus the possible savings with respect to fire doors!

Evolving tools of Quality Assurance

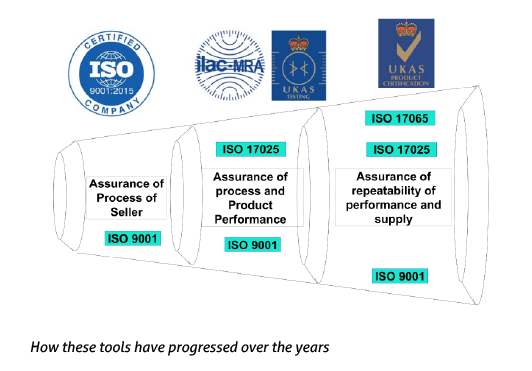

As the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) migrated to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in January 1995; businesses across 123 countries – all signatories to the formation – were enthused with the new opportunities this might open. ISO 9001, the 7-page standard originally published in 1987, when revised in 1994 became a standard of choice for everyone wanting to ride the wave of new possibilities. The standard defining requirements of Quality Management Systems become the most adopted standard around the world to set a benchmark for quality assurance. It helped in creating a common benchmarking tool for buyers and sellers providing a basis to contracts in ‘setting-the-standards’.

Compliance to the ISO 9001 opened doors for many businesses who grew beyond their existing set-ups. Along with the disruption of traditional supply chains of raw materials caused by this; suppliers of finished goods also needed to scale up as they were able to access new markets. The easiest way to validate the performance of goods from new suppliers was to get them tested. To demonstrate the repeatability of performance; industries started creating and relying on “Standards”. These were highly prescriptive documents setting out an agreed way of measuring, testing or specifying what is reliably repeatable in different circumstances and places .

As more inclusive standards evolved to validate the repeatability of performance of goods sold a new challenge came to fore. How to benchmark testing laboratories which were used to test whether the goods were ‘up-to the standards’? In 1999, the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) which had published the ISO 9001 published the ISO/IEC 17025 standard setting out the general requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories. This availability of compliance testing laboratories encouraged testing.

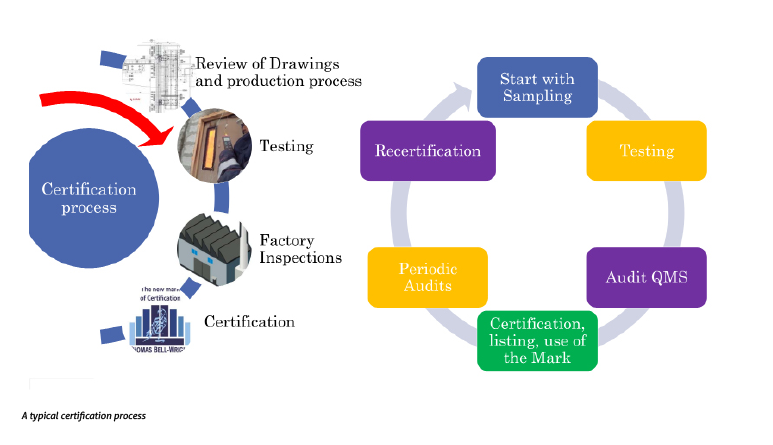

Increased failures brought about many other aspects of quality assurance in manufacturing and the realisation that reliance on only ‘Quality Management Systems’ was not enough. As the lack of quality assurance mechanisms hurt countries, institutions and businesses there was need for a better mechanism. This created a greater acceptance to concepts described in the ISO/IEC Guide 65 which was originally published in 1996. Now known as the ISO/IEC 17065, the standard sets the requirements for bodies certifying products, processes and services to objectively provide better assurance.

These certifications often provide means to verify the supply of goods using a certification mark and/ or a traceability code which can be verified on a public domain website or similar resource.

Using compliance terminology

The quality assurance section of a specification document is like the control panel which can be used to design and deliver the fire safety strategy correctly into the building. Vague, generic and unclear terminology used here opens the door for not only profit leakages and liabilities but also creates the possibilities of loss of life and property damage.

Two learning outcomes have been key across the investigations of several fire accidents. First is the dire need to establish a correlation between what was agreed to be supplied and what reached the construction site for installation. And the second being the requirement of qualified and independent inspection to verify the installation workmanship versus agreed installation methods. As the tools for addressing these two learnings have evolved well, the industry needs to quickly start using correct terminology to deliver fire compliance and achieve repeatability of product and service performances.